It’s so easy to take our big, beautiful bridges over the Shenandoah for granted these days—especially as we sit waiting for the light to turn, or zoom across with only our destination in mind!

(Does your family have old photos or stories about the earlier bridges? Share in the comments on Facebook, or stop by the Archives at Warren Heritage Society.)

It’s even easy to forget the previous truss bridges, which were a massive improvement in 1933. The older bridge structure was approximately 228-feet long, of which 150 feet contained the truss. The bridge deck contained 24 feet of clear width according to VDOT. The current bridge was built east of the truss bridge, which was then removed. The new structure is a 245-foot single span bridge with a deck containing approximately 40 feet of clear width.

Ho hum, right? The early bridges were celebrated with grand parades, and with good reason. Each bridge showcased the best engineering knowledge of its time and tremendously improved our ability to ship goods and to travel.

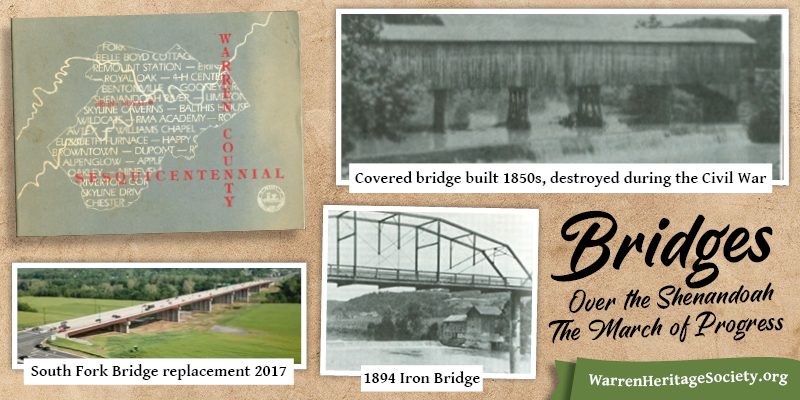

Here’s an old photo of a very early wooden bridge:

A passage from the Warren County Sesquicentennial book, one of the great sources of local history in the Warren Heritage Society archives.

Transportation On A Grand Thoroughfare

The Valley and the river formed a grand thoroughfare for travel on foot, on horseback and by canoe for numerous Indian tribes and for the following settlers, who added their wagons, boats and rafts to the traffic. The water-and-wagon traffic so closely associated with this area began in 1731 when Jost Hite and Robert McKay brought their wagon trains from Pennsylvania up the Valley to the confluence of the north and south forks of the river.

For more than a century the ferries and fords were the only way to cross the Shenandoah into the rich agricultural lands of the lower Valley. Four main ferries served the Warren County area: Chester’s at the confluence, Heath’s near Limeton, Hand’s near the present Front Royal Country Club and McKay’s across the South Fork at the present Page-Warren County line.

Thomas Chester received the license to operate his ferry “from the mouth of Happy Creek to the forks of the Shenando (Shenandoah) across the main river” in 1736, and put it in operation soon thereafter. For many years, it was the busiest ferry-raft in the area. As settlement and industry grew, farmers, manufacturers and lumbermen used the South Fork to ship their produce on the large rafts known as gundalows.

Wagon roads also took the natural routes. The Manassas Gap trail is followed today by Rt. 55 and Rt. I-66. The Chester Gap trail became Rt. 522 and the great trail up the Valley became Rt. 340.

The availability of good lumber and skilled carpenters rapidly made the area near Happy Creek into a thriving center for wagon construction. During the next century and until the railroads provided regular service three wagon makers, Trout, Cline and Fant, became widely known for their products.

The wagons even led to a major controversy over roads. Jost Hite wanted the main road from Chester Ferry to go through Manassas Gap for access to the coast. Thomas Chester wanted it to go through Chester Gap (a place named for him though he never lived there). The argument, intense because Hite represented the German element and Chester was backed by British interests, was settled by building both roads.

The first bridges across the river were wooden structures (covered bridges) built by the Front Royal and Winchester Turnpike Co. in 1854 and 1855. Meanwhile the railroad was inching its way into the Valley and eventually reached the village called Confluence (pre-Civil War name of Riverton). There the gundalows made contact with trains rather than with Potomac River boats at Harpers Ferry, making Riverton the terminus for Shenandoah shipping.

The Warren water-and-wagon business went downhill after 1854, when the first bridge was built and the first railroad arrived. Then the Civil War devastated the area. According to some reports, the wooden bridges were burned in 1862 by order of Gen. Stonewall Jackson. One personal report says they were destroyed by the flood of 1862. After the war the bridges were not rebuilt and the river traffic revived. But then the flood of 1870 left the river non-navigable except by small boats. The railroad took over.

Nevertheless, the Chester Ferry operated until new iron bridges were constructed in 1894. A Warren Sentinel report of 1877 tells of a four-horse team and wagon being washed downstream when the ferry was swamped, then being heroically rescued. A woodcut of 1884 shows the ferry still operating.

The iron bridges gave new life to Warren County. The formal opening was a great event. Ten thousand people attended. The parade included six bands, 500 horsemen, 100 horsewomen and 100 girls in fancy costumes.

Come visit Warren Heritage Museum on Chester Street and learn more!