As a friend put the question years ago, “Why are there so many native American place names here?” To her credit she figured out the answer on her own. But it’s easy to forget that we are not the first inhabitants of this lovely region.

Virginia is full of native American place names and our area is no exception – Powhatan, Rappahannock, Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Iroquois, Opequon, and more. They are all around us, yet it’s still hard to visualize the thriving native settlements that would have enjoyed living here.

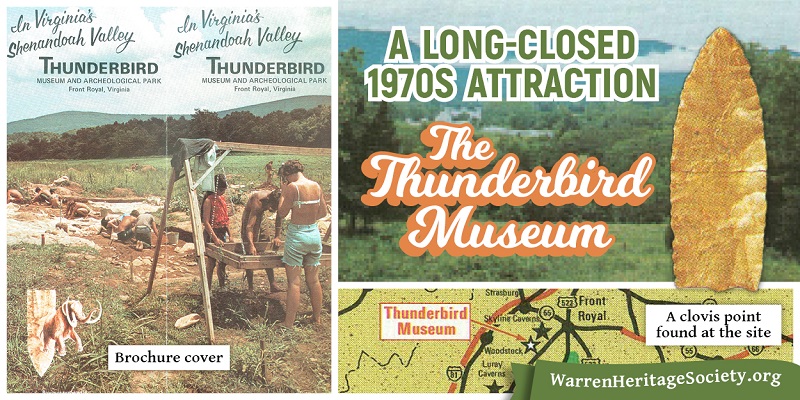

For a few years in the 1970s, there was a Paleoindian Site Museum just down the road near Limeton, Virginia, that explored that topic after archeologists found major artifacts.

The site is sadly closed to the public now but is a National Historic Landmark, and records describe an attraction we would have loved to spend time getting to know!

Did you visit this museum in the 70s? Do you have pictures? Tell us about your memories!

From the Wikipedia entry, “It is believed that the Thunderbird site had a large population due to the vast number of artifacts discovered. This contradicts earlier views that Paleoindian peoples lived in small groupings except for the occasional large gathering for a few weeks at a time to maintain kinship networks as well as share food source knowledge.”

From the Thunderbird Museum’s brochure

The Museum looks out across the South Fork of the Shenandoah River toward Massanutten Mountain.

When man first came to this area the mountains were snow covered year round and extinct animals such as mammoth, mastodon, horse and camel grazed on the grasslands of the valley floor.

Millions of years before this, oceans and shallow seas covered what was then a vast plain. Later great pressures in the earth resulted in volcanoes and mountains. Constant erosion carved the features we see today. Much of this is pictured and described in the Museum and outdoor exhibits within the park.

The major focus of the Museum is the history of man in the Shenandoah Valley. On exhibit are the tools used by man such as this 11,500 year old Clovis point. Other exhibits show how man’s technology and lifeways changed as he faced the challenge of the ever changing environment.

Nature trails within the Park pass by many natural features such as rock formations and caves. Outdoor exhibits on the trails tell the geological history of these features and describe the types of plants and the uses to which they were put by man. This particular cave is partially buried and will be excavated for it contains important records of the past.

From Sesquicentennial book

THUNDERBIRD MUSEUM AND ARCHEOLOGICAL PARK

The Thunderbird archeological site, now a National Historic Landmark, was discovered in the 1960’s by members of the Northern Shenandoah Chapter of the Archeological Society of Virginia.

In 1971, professional archeologists from Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., under supervision of Dr. William M. Gardner, began work at the site with National Geographic Society and National Science Foundation funding. In the same year, John Flynn, a local land developer, purchased the property.

Because of the considerable publicity generated as a result of the site’s antiquity and national significance, both Flynn and Gardner recognized the possibility of mutual benefits in a cooperative endeavor.

In the case of the former, it was felt the site’s prominence would help in promoting and selling the high density multi-use type of development envisioned. From the perspective of the latter, an opportunity was seen to preserve dozens of the hundreds of sites on the property as “green space” and at the same time generate funding for continuation of the research while presenting the results of the work to the general public.

Through this kind of interchange, the Thunderbird Museum and Archeological Park was born. Gardner and his students designed the museum and park exhibits while Flynn provided the property and funding.

Opened in June 1974, in a former house on 86 acres just outside of Limeton some six miles south of Front Royal on U.S. 340, the Museum has continued its original aims and is supported almost entirely by membership fees, donations and admissions.

Today, through a unique combination of indoor and outdoor displays, an interpretive nature trail and ongoing archeological excavations, the Museum visitor can virtually “live” over 11,000 years of Warren County’s early heritage. Virtually the entire history of the Museum and related excavations are unique and in their own way landmarks.

The “early man” (ca. 9000 B.C.) sites are perhaps the most important of their time and kind anywhere in the Western Hemisphere. The cooperation which developed between the archeologists and the initial developer was rare in the early 1970’s and is uncommon even today. The Museum was virtually the first of its kind and remains one of the few private institutions of this nature owned and operated strictly by archeologists.